The decline of local news is accelerating and costing you money

The number of local journalists in the U.S. has declined by 75% since the turn of the century, according to a new report. And that decline costs the American public dearly, in both access to information and money spent on taxes.

Shortage of local news

A joint project between Muck Rack and Rebuild Local News (RLN) tracked the number of journalists across the United States. Instead of looking at just the number of journalists, they used the ratio of the number of journalists in the area to the area’s population.

“We knew there was a local news crisis, but the scale of it was shocking, and how widespread it was, was a little bit surprising,” Rebuild Local News President Steven Waldman told Straight Arrow News.

“If you have a million people, you need more reporters than if you have 10,000 people,” Waldman continued. “When we’re looking at LA, they have way more reporters than a little county somewhere. But they also have way more people and more blocks and more neighborhoods and more schools, and more elementary schools and more of everything that needs to be covered.”

The report also found more than 1,000 counties, which represent about one-third of the counties in the country, lack the equivalent of a single full-time local journalist.

“News deserts” – a term defined as a community with limited or no access to credible and comprehensive local news coverage – might be expected in rural areas. But the report found similarly low densities of reporters in some of the nation’s largest markets: In Bronx County – home to 1.4 million residents, and separated from the media capital of the country by the 400-foot wide Harlem River – there are only 2.9 local journalists per 100,000 people.

Of the 48 counties with a population of more than 1 million people, only 14 have more local journalists than the national average of 8.2 journalists per 100,000 people.

A journalist who would have covered one county’s government in 2002 is likely “now covering four counties plus everything else that they’re doing,” Woodward told SAN.

“It’s inevitable that’s going to mean that they’re spending less time per story,” Woodward continued. “And that’s going to mean they’re more superficial.”

Changing newsrooms

As newsrooms have stretched resources, many have had to do away with specialized reporting.

“We no longer have people doing beats, so we don’t have somebody who works the cops, somebody who works education,” said William O’Neil, a North Carolina reporter who retired in December after 45 years in local journalism. That shift toward more generalized reporting can erode the level of trust between sources and journalists, O’Neil told SAN.

O’Neil spent much of his career at WXII-TV in the Piedmont Triad area of North Carolina. Over the years, O’Neil said he watched the number of reporters at the Capitol building in Raleigh dwindle, even as the news continued to flow in the swing state with a $30 billion annual budget.

“We have a handful of reporters covering that beat. It just doesn’t make any sense,” O’Neil said. “But it’s not great TV. We want car chases, we want fires, we want all that other crazy stuff. Forget about that our lives are being dictated by a group of people down at the legislature who are controlling the money, controlling voting, controlling all kinds of things for their political advantage. And we just don’t have the people there anymore who are covering it, and I think it’s a shame.”

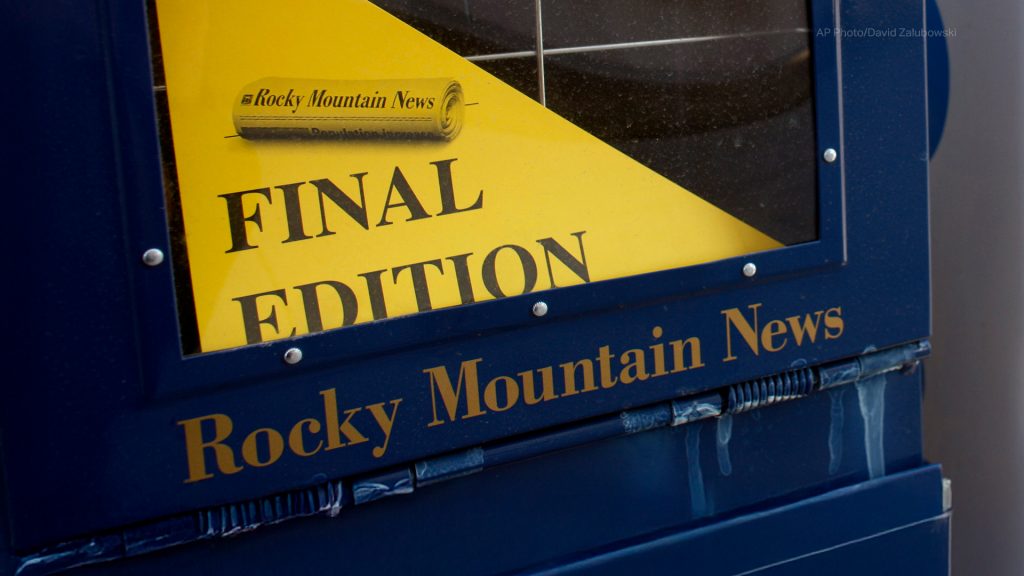

O’Neil experienced some cuts in his TV newsroom. But he said, local newspapers have taken the hardest hits.

Why is this happening?

A recent study from Harvard University found that more than half of the nation’s nearly 700 major daily newspapers are owned by just a few major parent companies, including Gannett, Lee Enterprises and Alden Global Capital.

That comes at a cost.

Baltimore Banner reporter Céilí Doyle described Alden as “a pretty nasty hedge fund group that has a reputation for buying up local newspapers, bleeding them dry, and, you know, just collecting, excavating whatever profit they can get out of them.”

Alden continues to buy papers, recently purchasing six publications in the San Francisco area.

“It’s really troubling and scary when you see this,” Doyle told SAN. “The best you can hope for, I guess, is a benevolent dictator.”

Woodward had similar thoughts on many of these ownership groups.

“Their business model is not to improve the service to communities,” Woodward said. “They’re squeezing these things to get as much profit out of them as they can on the way down.”

One of the Alden Group’s biggest papers is the Chicago Tribune, which the hedge fund bought in May 2021. Two days after the acquisition, Alden announced a large round of buyouts.

Doyle now works in Baltimore but grew up in Chicago.

“Basically, every journalist that I grew up reading and respecting has left that institution, and it’s really become a shell of itself,” Doyle said about the Tribune.

Alden’s 2021 purchase also included the Baltimore Sun, a major metropolitan daily paper that has won 16 Pulitzers over the years, most recently in 2020. When Alden came to town, a group of Baltimore reporters concerned by the hedge fund’s reputation for drastic downsizing sought out other potential owners.

One of those contenders, Stewart Bainum, lost his bid to buy the Sun. Then he came up with a new idea: Launch a nonprofit newsroom to compete with the storied daily. The Baltimore Banner was born in 2022; this year, it won its own Pulitzer.

“I think we’ve seen nonprofit newsrooms try to pick up the embers of what used to be these really big, traditional news organizations and do their best to fill in the gaps,” Doyle said. “Whether it’s something like a national nonprofit Report for America, or it’s these smaller, regional-based things like the Baltimore Banner.”

Even if the Banner is “smaller” than legacy operations, it still requires a lot of money to operate. The newsroom was launched with a $50 million pledge and operates on an annual budget of about $15 million. That’s a lot of money for an industry that has been hit with a steep decline in ad revenue.

“TV stations used to print money in the basement,” O’Neil told SAN. “They’re not doing that anymore. Things have gotten much tighter. There’s so many more channels to watch, and people are watching them.”

Broadcast TV and radio are forecasted to lose 10% of their advertising dollars this year compared to last year, according to an S&P Global Market Intelligence report.

“The advertisers have moved to digital solutions, whether it’s Google or Facebook or LinkedIn or Auto Trader, all those different things that used to fuel local newspapers and TV stations,” Woodward said.

Straight Arrow News has reached out to Alden Global Capital for comment but has not yet heard back.

The cost to you

The community impact of a decrease in local journalists can be measured in different ways.

“You don’t have the information to know who to vote for, there’s more corruption,” Woodward said. “There’s all sorts of studies that’s shown if you don’t have local news, you have more corruption and worse city services and lower bond ratings, even higher taxes, less civic participation, things like that.”

It also affects how tax dollars are spent.

A report from Bloomberg shows government costs increased in cities where newspapers closed. The report found that three years following newspaper closures, the costs for municipal bonds and revenue bonds increased for those cities.

Cities often use bonds to pay for big public works projects.

“We as a public are suffering,” O’Neil said, “Any kind of a good government needs to have journalism. It’s a part of our democracy, and we are just doing, I think, a lesser job than we ever did.”

Investigative stories have helped taxpayers save millions of dollars nationwide. For example, a decade after the city of Bell in L.A. County lost its local newspaper in 1998, the LA Times found the salaries of the city manager and police chief had been raised exponentially, costing taxpayers $5.5 million.

How do we fix it?

Former Baltimore Sun reporter David Simon once said, “high-end journalism is dying in America and, unless a new economic model is achieved, it will not be reborn on the Web or anywhere.”

While local journalism can save the public money, journalism itself requires money.

“The reality is that some of this really should just be viewed as a civic good, as something that just has to happen for the health of a community,” Woodward said. “That’s a classic type of function that needs support from philanthropy.”

Woodward also believes the industry could benefit from more government support, particularly through civic service initiatives.

In 2025, lawmakers in Washington state introduced a bill that would create a grant program to support journalists covering civic affairs.

Nonprofit newsrooms, like the Baltimore Banner, are becoming more common. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Tulsa Local News Initiative is hiring reporters for the launch of its nonprofit outlet this fall. A similar effort is also underway in Los Angeles. Newcomers can’t replace the thousands of local newspapers that have folded in recent years. But they can fill some gaps.

O’Neil told SAN that he believes the broadcast media needs to market the business better and shift coverage.

“If you’re reporting today on telling your viewers to drink more water because it’s hot outside, guess what: That’s why nobody’s watching your damn newscast,” O’Neil said. “Because you’re telling them crap that they heard 25 years ago, and it’s just not relevant today.”

Doyle also pointed to non-traditional forms of media and having legacy media embrace them.

“I do think investing in untraditional or nontraditional ideas of what news is, is going to be the thing that saves this industry,” Doyle said. “It’s the people who want to be innovative, the people who see how information is delivered now, whether that’s through influencers on TikTok [or] these little bite-sized nuggets. We have to adapt.”