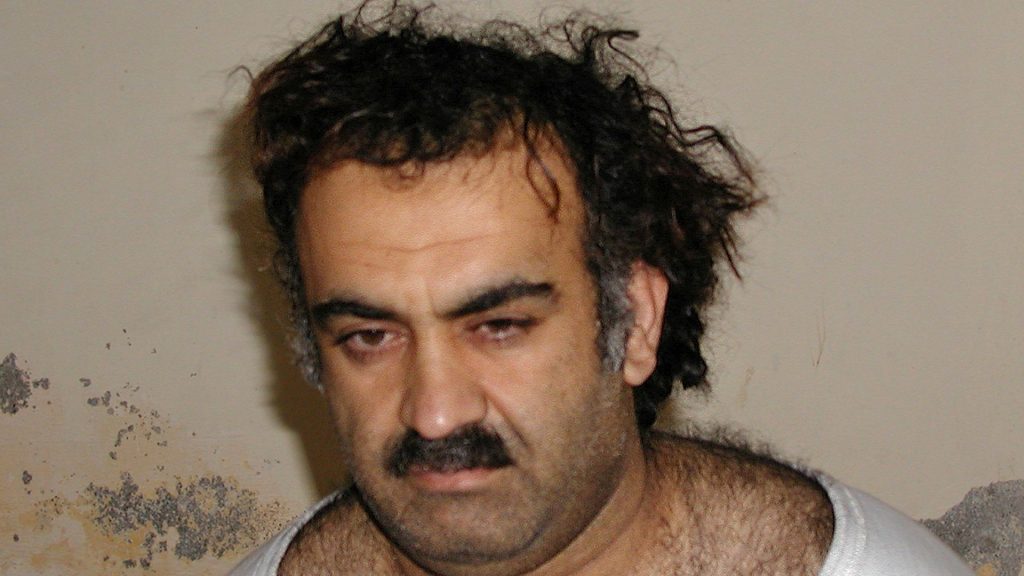

Court tosses plea deal for alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed

On Friday, July 11, a federal appeals court in Washington, D.C. tossed out a plea deal that would have spared the lives of the alleged masterminds behind al-Qaida’s Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks on the United States. Under the plea deal, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and two co-defendants would have received life sentences without the possibility of parole rather than the death penalty in an agreement between the prosecution and defense that was worked out over two years.

Long legal battle over 20 years

The U.S. military has been trying to prosecute Mohammed and the other defendants for more than 20 years. However, the legal process has been slowed by various legal challenges.

Under the Biden administration, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin rejected the proposed plea deal, arguing only the defense secretary should have the authority to decide whether the death penalty should be considered in a case as serious as the Sept. 11 attacks.

Court rulings on authority to cancel plea deal

In December, a military appeals court ruled against Austin’s attempt to cancel the plea deal. On Friday, a three-judge panel from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit sided with Austin in a 2-1 decision, ruling that he did have the authority to cancel the agreement.

Mohammed’s defense lawyers argued that some of the evidence was obtained through torture, and questioned if that evidence is legal or ethical to use in court.

The 9/11 attacks and victims’ families’ reactions

Mohammed is accused of being the person who planned and oversaw the 9/11 terror attacks, when hijackers crashed planes into the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Another hijacked plane, which was also part of the plot, crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers tried to retake control from the hijackers.

Family members of 9/11 victims had different opinions about the proposed plea deal, the Associated Press reported.

Some opposed it, believing that a full trial would be the best way to achieve justice and learn more about what happened. Others supported the deal, thinking it might be the fastest and most realistic way to end the long process and possibly get answers.