A student’s death reshaped Texas school safety, but many states lack similar laws

In August 2024, 14-year-old Landon Payton died after suffering a medical emergency and collapsing in his middle school gymnasium in Houston, Texas. Nearly a year later, local families, lawmakers and advocates still wonder whether his life could have been saved by a functional automated external defibrillator (AED), which treats cardiac arrest by sending electric shocks to the heart, or by CPR, had the school nurse been mandated to master the technique.

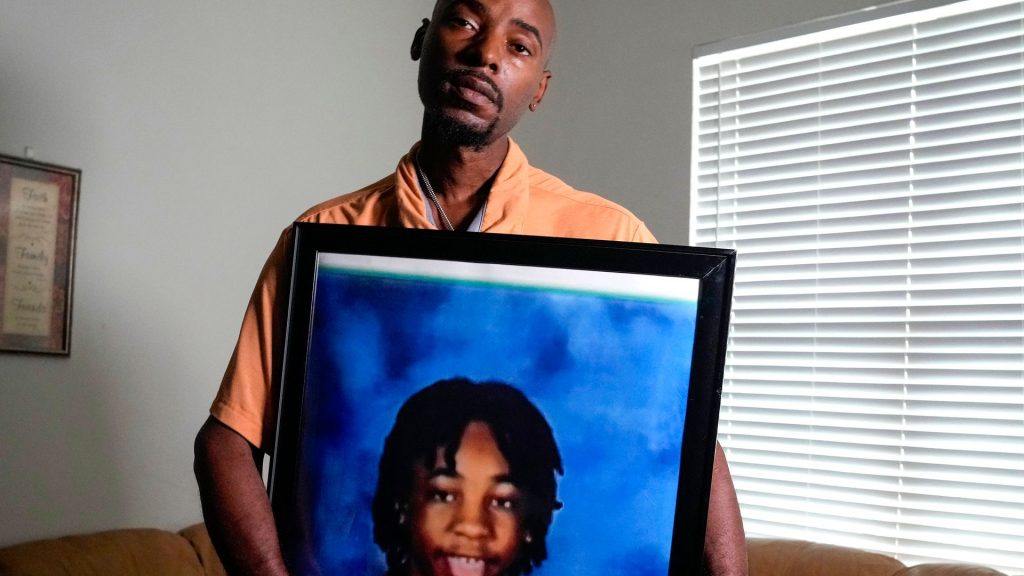

The Houston Federation of Teachers union and a lawyer representing Payton’s father said the school’s AED wasn’t working when a campus nurse attempted to revive Payton in the gymnasium. While the Houston ISD leaders still haven’t validated these claims, Payton’s death rocked Texas’ largest school district and spurred legislation to improve students’ chances of surviving cardiac emergencies on campuses.

Texas schools will soon be required to certify more employees, including school nurses, in CPR, implement annual cardiac arrest practice drills, inspect AEDs more frequently, and create a “cardiac emergency response plan” and team to respond to cardiac emergencies, among other requirements.

Payton’s death and Texas’ response reinforce what cardiac awareness advocates have spent years repeating: Simply having AEDs isn’t enough to save lives — schools must ensure they work and have a detailed plan for using them. Still, only a third of states have similar laws. The reason for the rarity, advocates said, is because states often don’t see hunger for change until tragedy strikes or are held back by cost concerns.

“Having the devices is important, but it is even more important to have that plan in place,” Martha Lopez-Anderson, executive director of cardiac death prevention advocacy organization Parent Heart Watch. “Unfortunately, in many cases, the AEDs are either not accessible, the battery is dead or the packs are expired. By having those plans in place, written and well-practiced, that’s how we are going to minimize these things from happening.”

Roughly 23,000 students experience cardiac arrest in a location outside of a hospital each year, according to the American Heart Association. And having a detailed school cardiac emergency response plan in place, including regular equipment checks, increases a student’s chance of survival by 50% or more, according to the association.

Though stricter preparation has shown to make schools safer, similar laws have yet to be passed in nearly three dozen states, largely due to cost concerns, said AHA communications director Shelly Hogan.

On top of purchasing hoards of AEDs, which often cost several thousand dollars each, properly training staff and developing cardiac emergency drills requires devoting resources that can add up for schools with limited budgets.

“As with all policy change campaigns, resistance to change does happen, especially when states are requiring local schools to do something that they currently may not be doing,” Hogan said. “That said, we have seen states across the country enthusiastically pass this policy.”

Tightening training

At the time of Payton’s death, Texas was already considered more proactive than other states in preparing schools to handle sudden cardiac arrest. Texas law required all schools to have at least one AED on campus. Houston ISD, the district in which Payton died, had an average of three AEDs at each of its 270 schools.

Democratic State Sen. Carol Alvarado, who sponsored the Texas bill named in Payton’s honor, claims that since the nurse at Payton’s school didn’t know CPR, Payton didn’t receive any treatment until paramedics arrived at the campus.

Houston ISD leaders still have not confirmed exactly what life-saving measures school staff took when Payton collapsed. They did, however, share that 1 in 6 of the district’s 1,038 AEDs weren’t working at the time of the tragedy — revealing shortcomings in the state’s preparation requirements.

“Even when I started talking about the bill, most legislators said, ‘Well isn’t it mandatory that nurses have to know CPR?’” Alvarado told Straight Arrow News. “I said ‘no.’ And so it garnered a lot of bipartisan support.”

Now, Texas school employees will be trained to react much differently in the case of a similar emergency.

Pending a signature from Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a bill approved by lawmakers mandates that more school staffers have to obtain certification in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and AED usage, including school nurses and their assistants, athletic coaches, physical education teachers, marching band directors and more.

In addition to creating a detailed cardiac emergency response plan, schools will now have their AEDs inspected during fire safety inspections, ensuring they’re in working order, and staff will institute drills to practice their new plans at least once each year.

Plus, schools will be required to purchase enough AEDs to ensure an apparatus can be used within three minutes of the start of an emergency at any location on campus, a key facet of national cardiac emergency response plan recommendations.

“Of course, it doesn’t bring back Landon, but hopefully we can prevent another death,” Alvarado said.

Finding the funding

Though much smaller an investment than many school safety measures, the cost of ensuring schools across the country are similarly well-prepared for cardiac emergencies can vary widely, and local districts are typically left to foot the bill.

“Financial concerns are a leading barrier we work to address,” Hogan said. “The acquisition of AEDs and their regular maintenance is a hurdle, and can require substantial funding, especially for large schools.”

The cost of a single AED ranges from $1,200 to $3,000, according to the AHA. Costs can stack up for maintenance and replacement — AED parts often have a multi-year lifespan and must be regularly reviewed and replaced. Training and certifying staff typically costs $30-80 per person, Lopez-Anderson estimated. National guidelines recommend 10% of a school’s staff comprise the cardiac emergency response team.

Texas’ new requirements — like in many other states — do not come with dollars attached. Lawmakers expect schools to absorb the costs of implementation, but didn’t estimate how much that could be. Often referred to as “unfunded mandates,” such laws can be unpopular among school leaders.

“We have effectively countered this (financial) barrier by suggesting that schools already have emergency plans in case of fires, tornadoes, and other emergencies,” Hogan said. “We are hopeful that this planning becomes a regular part of the emergency planning that schools already must do.”

To get there, the AHA and advocacy organizations like Parent Heart Watch have focused on advocating for state and federal appropriations to be tied to legislation.

For example, Virginia’s law, passed in 2024, will appropriate $250,000 yearly to be distributed as grants for high-need schools to purchase AEDs and establish training. New Mexico appropriated $150,000 to help facilitate training in rural schools.

Advocacy organizations are also working to establish a grant program through the federal HEARTS Act, to increase funding to schools that want to be better prepared.

Lopez-Anderson, who lost her own child to sudden cardiac arrest, hopes that AED maintenance and training will someday have a line item in all school budgets, like chalkboards and desks.

“But unfortunately, there’s always a sentinel event that triggers the introduction of a bill,” Lopez-Anderson said. “There is a lot of advocacy being done. A lot of people who have been personally affected, who went to their legislature and said, ‘Hey, now it’s time. We got to do this.’ Because we’ve learned lessons and we’re learning that not having this plan in place, it’s a problem.”